Book Reviews

Music Charts Magazine Book Reviews

Date = 19 October 2015

Author name = Amanda Petrusich

Title = Do Not Sell at Any Price: The Wild, Obsessive Hunt for the World’s Rarest 78 rpm Records

Publisher = Scribner

Review =

Until the advent of digital technology, people born after approximately 1950 bought music pressed on vinyl. Before mid-century, though, music was released on shellac, usually ten-inch brittle records that rotate at 78 revolutions per minute—give or take a revolution—and that contain about three minutes of performance per side. The time limitation was both negative and positive. Unless records were stacked on a spindle, listeners needed to tend to a record after each playing, which was cumbersome and time consuming. Yet the time constraint forced one to focus on the music and become familiar with it, a reality that does not exist when listening at one sitting to a complete LP or CD; attention wanes. In some circles, 78s have nostalgic appeal, as evidenced by the occasional DJ playing only 78s on vintage equipment at parties. In 2010 Tom Waits and the Preservation Hall Jazz Band recorded two tunes that were released on a 78, though its material was vinyl, not shellac.

Because shellac is fragile and because 78s were last mass produced in the mid-1950s, they are increasingly rare. This might not much matter in one sense because a substantial amount of the music initially released on 78 is available on-line, and, in truth, some of it, especially the mediocre popular music from the 1950s, was so ordinary that its preservation hardly matters. (With some embarrassment I admit to buying, during my teenaged years, 78s by the likes of Teresa Brewer [“Music, Music, Music”] and Eddie Fisher [“Oh! My Papa”].) Blues recordings made primarily during the 1920s and 1930s, as well as Cajun and country musics and recordings from Greece, Albania, and a few other countries from this same period—all 78s—are a different matter, as Amanda Petrusich explains in Do Not Sell at Any Price, published in hard cover in 2014 but recently released as a paperback.

Yes, used 78s can still be found at estate and garage sales as well as in thrift stores, and can be purchased inexpensively because there is a limited market for them. Rare and valuable 78s—such as those about which Petrusich writes—are not found in such places because the market for them has been cornered by a handful of passionate, voracious collectors. By focusing on these men and their pursuits—adventures is probably a better word—and what they taught her, Petrusich crafts a narrative that, while it discusses recording realities, focuses on what happened to records after they were released and their effect on this handful of dedicated men. (The author investigates why men dominate this activity.) Along the way, she becomes enamored of and transported by much of this old music that is new to her.

Petrusich lauds collectors as preservationists without whose efforts a significant segment of (mostly American) music might have been lost. One of them, John Tefteller, not only located and bought the only known photograph of Charley Patton, but he also discovered and purchased the only known copy of King Solomon Hill’s 1932 recording of “My Buddy Blind Papa Lemon.” Tefteller relates that in making these purchases “the hundred dollar bills came spilling out of my wallet,” to which Petrusich wryly responds, “It’s the sort of thing that makes you want to buy a man a cheeseburger, or at least tell him thanks” (103). Now, because of the willingness of Tefteller and others to share even their rarest items (though not by lending them), almost every recording Petrusich discusses is available at youtube.com, including “My Buddy Blind Papa Lemon.” As a result, when reading about her response to a recording, one can, after a few keystrokes, listen to it on a computer and compare one’s own reaction with hers. Granted, listening to the music this way is aesthetically inferior to hearing it on a 78 played on appropriate equipment, but there it is, ready to be enjoyed at no cost, courtesy, ultimately, of the collectors.

With one exception, the collectors Petrusich describes were previously unknown to me. The exception is Harry Smith, an odd-ball collector (most of the collectors are odd to one degree or another, though he seems odder than most) known for Anthology of American Folk Music, which he prepared for Folkways Records. Released in 1952, this idiosyncratic and influential collection—it helped inspire the folk revival of the late 1950s and early 1960s–presents music from the period 1927-1932, all drawn from Smith’s collection. Long available on CDs, the anthology influenced numerous musicians, including, according to Smith’s friend Allen Ginsburg, Bob Dylan, Ramblin’ Jack Elliott, Jerry Garcia, and Peter, Paul, and Mary. Following Smith’s death in 1991, his collection of over 13,000 78s disappeared, despite his having left most of his recordings to the New York Public Library.

Less eccentric than Smith but eccentric nonetheless, Joe Bussard is another of the collectors—perhaps the greatest collector—Petrusich presents. She did not know Smith; she knows Bussard, who owns twice as many records as Smith did. A gruff man of strong opinions (real jazz ended in 1933; country music, in 1955; bluegrass, in the late 1950s), he made one of the most impressive purchases of all time. This occurred when, on a 1966 record hunting expedition, he picked up a man walking along a road who told him that he had many old records. Bussard drove him home, where the man produced, among other things, fifteen Black Patti 78s. No known original Black Patti recording exists in more than five copies. Bussard bought all the records for $10. When word of this purchase got out, for just one of the Black Pattis—possibly the only known copy of “Original Stack O’Lee Blues,” by the Down Home Boys—Bussard received offers of up to $50,000, which he declined. Petrusich tells several fascinating, even gripping stories such as this, though none is quite so dramatic.

None, that is, except for an exploit of her own, which concerns the innocuously named Wisconsin Chair Company, located in Port Washington. In the second decade of the twentieth century it began selling phonograph cabinets, which consumers considered furniture. Soon, the company began making phonograph machines to place in the cabinets, and then, in 1917, started producing records, sold in furniture stores, to be played on the machines. They were pressed at a plant in Grafton, WI, the town where the company established a recording studio in the late 1920s. Music was released on several labels, the main one being Paramount. After the company struggled for a few years while selling popular music, in 1922 executives decided to focus on race music, as it was called—music, mainly blues, that was performed by and that appealed to blacks—though it also released other kinds of music, including country by the likes of the Dixie String Band and the Kentucky Thorobreds. Blues performers who recorded for Paramount include Son House, Skip James, Blind Lemon Jefferson, Charley Patton, and Ma Rainey. Made cheaply with inferior material, the records were released in small numbers, typically around 1,200 for each 78. Over time, the combination of poor material and few copies caused Paramounts to become scarce. Petrusich wonders—as others have wondered—what happened to the unsold records and the metal masters from which they were pressed. One rumor: they were thrown into the Milwaukee River, which flows past what was the Grafton plant. In an action that at least shows her commitment to her project, the author took scuba-diving lessons so she could search the river for something—anything—related to Paramount. She tried but failed, which could also be said of collectors’ occasional attempts to find and buy records. Her effort shows dedication, or foolhardiness, or both.

The author writes deftly about Tefteller, Smith, Bussard, and others, including herself. An outsider pleased to be introduced to and more-or-less respected by a small group of obsessive men, she marvels at what she learns and grows fond of her new acquaintances. With one collector in particular, Christopher King, she develops a genuine friendship, one that goes beyond their professional relationship. King, who introduced her to Bussard, is so committed to understanding the music he loves that, in order to write accurate liner notes for a collection of performances by the Greek violinist and murderer Alexis Zoumbas, he traveled with his family to Greece to research the musician’s life. Spending considerable money to feed his passion seems not to bother him, as may also be deduced from his willingness to pay Bussard at least $5,000 for two recordings of Cajun music—recordings he already has—because Bussard’s copies are in slightly better condition than his own. And by playing Zoumbas’s music for the author, King inspired her to write this: “And I understood, for a moment, what collectors meant when they moaned about what was lacking in contemporary music: that pure communion, that unself-consciousness, that sense that art could still save us, absolve us of our sins” (197). This statement might also partly explain the fanatical dedication to collecting by King and his associates. Yes, there is excitement in the chase, in the pursuit, and it doubtless becomes addictive. Still, there is an aesthetic reality underlying the quest, perhaps most vividly presented here in the actions of Bussard as he listens to his records in the company of King and Petrusich. He cannot sit still; he must move: “At times it was as if he could not physically stand how beautiful music was. It set him on fire, animated every cell in his body” (206).

Not only does Petrusich master an arcane topic, but she presents her material engagingly. The narrative is enhanced by an agreeable first-person voice. The reader—this reader, anyway—would like being in the company of the woman who created it. Her prose sparkles, especially when creating similes. When “like” or “as” introduces a comparison, a cliché often follows. Not so with Petrusich. Here are a few examples of her inventiveness. Listening to an analog recording on a good stereo—as opposed to hearing music on MP3–is “like delicately consuming a fancy French chocolate when you’ve only ever gnawed on Hershey bars in the parking lot of a Piggly Wiggly” (17). Accompanying Chris King as he looks for records at a flea market “is oddly thrilling, like getting tied to the back of a heat-seeking missile” (47). On seeing the Charley Patton photograph that John Tefteller discovered: “It was like looking up from a campfire, tugging a marshmallow off a stick, and spotting Bigfoot casually leaning on a pine tree outside your tent, waiting for a s’more” (101). On listening to two recordings by Alexis Zoumbas: they “sounded like someone being turned inside out, with every single one of his organs suddenly exposed to cold air” (197). A terrific writer, Petrusich has produced a masterful book.

Author = Benjamin Franklin V

Date = 7 October 2015

Date = 7 October 2015

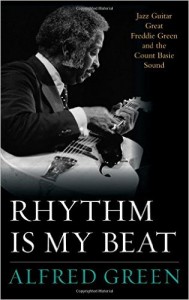

Author’s name = Alfred Green

Genre = Jazz

Title = Rhythm Is My Beat: Jazz Guitar Great Freddie Green and the Count Basie Sound

Publisher = Rowman & Littlefield

Review =

Published in the series Studies in Jazz overseen by the Institute of Jazz Studies at Rutgers University, Rhythm Is My Beat documents the career of Freddie Green, seemingly universally acknowledged as the greatest rhythm guitarist ever, in any genre. His genre was jazz. Because the author is the musician’s son, readers might expect mawkishness, but the text is neither sentimental nor particularly emotional. It provides biographical details in a straightforward manner, never milking them for effect. Once Alfred Green begins discussing the guitarist’s career, however, details about his father’s private life decrease significantly.

In focusing on music, not biography, Alfred Green presents a good overview of his father’s career, almost all of which—half a century–was spent with the band of Count Basie (thus, the book’s subtitle). He begins strongly by using photographic evidence to prove that in early 1937 his father played at the Black Cat Club in New York City with a group led by saxophonist Lonnie Simmons, a friend from South Carolina. (Green was from Charleston.) Because Green left relative anonymity with Simmons for the big time with Basie, details about the Black Cat engagement are important; they are also sometimes misunderstood. In the autobiography John Hammond on Record (1977), impresario Hammond states that Green worked at the Black Cat with the group of Skeets Tolbert, not Simmons, a claim repeated by some jazz writers because Hammond was in a position to know: he discovered Green at the club, thought him a good fit for Basie’s rhythm section, and introduced him to Basie. In other words, he was instrumental to the careers of both Green and Basie. Yet in identifying the group with which Green played at the Black Cat, Hammond is demonstrably wrong, as Alfred Green proves. He sets the record straight.

Anyone familiar with Basie’s band from 1937 until the leader’s death in 1984 and beyond it to Green’s death in 1987 will necessarily know the contour of Green’s career because of Green’s long, almost unbroken tenure with the leader, beginning in 1937. “Almost,” because of occasional illness, but also because Basie bowed to economic and musical realities (accommodating the new music known as bebop) by reducing his band to a small group in 1950, one that initially excluded Green. About two months later, though, the guitarist joined it, apparently by insisting that Basie employ him. At the urging of Billy Eckstine and Basie’s manager Willard Alexander, Basie discontinued the small group and by 1951 reconstituted a big band, which included Green. This organization relied more heavily on written arrangements (by the likes of Neal Hefti and Ernie Wilkins) than had previous versions of the band, which often played head arrangements (those that are spontaneous, or played from memory). Yet whether Basie led a relatively unrestrained band or one controlled by formal arrangements—or fronted no more than ten musicians—Green was, with a few brief exceptions, a constant, providing a dependable 4/4 beat that, with the remainder of the rhythm section, made the band swing. Not only did he create the beat, but when a musician violated it or was less than decorous on stage, he expressed dissatisfaction by glaring at the offending party with a gaze known as “the ray.” In so doing, he served as an enforcer, as the person who insisted that the band’s musicianship and integrity be maintained.

Despite being known primarily for his association with Basie, Green had a musical career apart from him, as the author documents in a discography of thirty-four unnumbered pages. Green was attractive to other musicians for the same reason Basie valued him: his ability to provide a steady beat. As a result, he performed on hundreds of recordings as sideman, beginning with Teddy Wilson and Billie Holiday in 1937 and concluding with Diane Schuur three days before his death at age seventy-five. He played at numerous sessions led by Basie’s instrumentalists, such as Buck Clayton, Paul Quinichette, and Lester Young, but also at ones led by musicians who had not been regulars with Basie, including Mildred Bailey, Ruby Braff, Bob Brookmeyer, Ray Brown, Benny Carter, Al Cohn, Nat Cole, Roy Eldridge, Coleman Hawkins, Woody Herman, Illinois Jacquet, Gerry Mulligan, Buddy Rich, Tony Scott, Sonny Stitt, Sir Charles Thompson, and Sarah Vaughan. With some of these and other leaders he participated in recordings that have proved enduring, including “This Year’s Kisses,” with Wilson and Holiday (1937); “A Sailboat in the Moonlight,” with Holiday (1937); “Ad-Lib Blues,” credited to Benny Goodman, though the clarinetist does not play on it (1940); Charlie Parker’s album Night and Day (1952); Sing a Song of Basie, by Lambert, Hendricks, and Ross (1957); and Ray Charles’s Genius + Soul = Jazz (1960).

Most important for his playing, Green also composed tunes, two of which are popular in jazz circles: “Down for Double” and “Corner Pocket”; the latter has been recorded over a hundred times, sometimes as a vocal titled “Until I Met You.” Alfred Green relates an engaging anecdote about what inspired Manhattan Transfer to record this piece, its version of which won a Grammy (130-31). The book includes an apparent contradiction about the number of tunes Green wrote. The author states that his father composed “in excess of thirty tunes” (132), but Mark Allen, who compiled the list of Green’s compositions that appears in appendix K, records only twenty (239-41). One wonders why, if Green wrote at least thirty, Allen fails to account for the other ten or more. Alternatively, Allen could be accurate and the author is mistaken. Alfred Green should have resolved this issue.

Green’s narrative constitutes a little over half of this 325-page book. Fourteen appendices compose most of the other pages. The appendices consist mainly of essays—mostly (all?) by authors other than Green—about the guitarist’s technique and style that will likely interest musicians, not ordinary readers. Photographs enhance the book. Candid shots, which are especially appealing, show Green in a street scene looking dapper, seated at a club with Billie Holiday and Lester Young, pretending to fight the boxer Sugar Ray Robinson, golfing separately with Billy Eckstine and Joe Williams, and, in a beautiful picture, shaking hands with President Reagan at the White House. There are many others.

Though Green adequately chronicles the career of an important musician, his text has problems. When using the word “always,” for example, he does not allow for exceptions when exceptions clearly exist, as when stating that “John Hammond was always on the prowl” (47) and that Lester Young played “to a meter that was always a fraction-of-a-beat ahead of him” (58). Hammond never slept? Young never played on the beat, even in ensemble passages? Green offers opinions as facts, as when claiming that Jimmy Rushing was “the best blues singer around” (74) and that saxophonist Frank Wess was “incomparable” (77). Though the author documents many of his statements, he sometimes fails to do so when proof is needed, as when stating that “Lester Young struggled to keep his emotions intact” following the death of saxophonist Herschel Evans and that, as a result, saxophonist Jack Washington “often had to help the distraught [Young] to the stage and his seat” (59). Green is sometimes credulous. Does he really believe that bandsmen “peed from the moving bus with the door partially open” (78)? (Try imagining it.) Or that, despite the claims of Frank Wess and Benny Powell, an opened can of sardines fell from an overhead bus rack and landed on singer Joe Williams’s head, where it remained for the remainder of the trip (81)? On the topic of music, one wonders why Green characterizes Dizzy Gillespie, Fats Navarro, and Charlie Parker as hard-bop players (98) and why, other than listing it in what is termed a “selected discography,” he ignores The Atomic Basie (1957), arguably the most impressive post-war Basie big band album. Identifying Ruby Braff as a “neo-Dixieland trumpeter” disserves the musician (246). Most disconcerting, though, are constructions such as these that, first, use the wrong case and, second, feature a dangling modifier: a “tiff between he and Hammond” (68) and “In interviewing John Williams . . . , the twenty-five-year Basieite once asked me . . .” (91). Because Green was unaware of these problems, his editor should have corrected them.

In sum, Alfred Green adequately summarizes his father’s career without getting bogged down in details or becoming technical when discussing music. That is, general readers can enjoy the book, though they will be distracted by writing lapses such as those mentioned here.

Author = Benjamin Franklin V

Author = Arlene Corsano

Genre = Rhythm and Blues

Title = Thought We Were Writing the Blues but They Called It Rock and Roll

Publisher = ArleneChristine

Review =

Thought We Were Writing the Blues but They Called It Rock and Roll chronicles the career of Rose Marie McCoy (1922-2015), about whom one could be excused for asking, “Rose Marie who?” Though she considered herself primarily a singer and secondarily a composer, her legacy rests with the hundreds of songs—over 800–she wrote, though none became a substantial hit. This reality resulted not from her lack of talent but from the fact that she mainly wrote blues that were performed in the rhythm-and-blues mode by blacks for black audiences at a time when mainstream culture, including music, was dominated by whites because of social realities. Yet with her intended audience, McCoy succeeded. A veritable who’s who of rhythm-and-blues performers recorded her tunes (though adept at writing both music and lyrics, she collaborated on most of her creations), including Faye Adams (“It Hurts Me to My Heart,” which reached number one on the rhythm-and-blues charts), Big Maybelle (“Gabbin’ Blues,” featuring McCoy’s speaking), Nappy Brown (“Don’t Be Angry”), Ruth Brown (“Mambo Baby”), the Du Droppers (“Talk That Talk”), the Five Keys (“Don’t You Know I Love You”), Little Willie John (“Letter from My Darling”), Louis Jordan (“If I Had Any Sense”), Joe Medlin (“No One but You”), Little Jimmy Scott (“I’ll Be All Right”), Shirley and Lee (“Keep On”), the Thrillers (“Lizabeth”), and Big Joe Turner (“Well All Right”). All these songs were recorded in the mid 1950s, her most creative period. Subsequently, her compositions were recorded by such singers as Maxine Brown (“See and Don’t See”), Jerry Butler (“Got to See If I Can’t Get Mommy [to Come Back Home]”), Nat Cole (“My Personal Possession”), Al Hibbler (“Stranger”), Liz McCall (“Double Determination”), Ike and Tina Turner (“It’s Gonna Work out Fine”), Sarah Vaughan (“I Need You More Than Ever Now”), Lenny Welch (“Hundred Pounds of Pain”), and Jean Wells (“Ease Away a Little at a Time”). Her most recent compositions to be recorded were written with Billy Joe Conor for his debut CD (2013).

“Trying to Get to You” deserves special comment because of its historic importance. Composed with Charlie Singleton (to whom Corsano’s book is dedicated) and recorded initially in 1954 by the Eagles (not the current group of this name), Elvis Presley covered it the next year on his first album, Elvis Presley. Because this release includes songs written by blacks (such as “I Got a Woman” [by Ray Charles and Renald Richard], “Money Honey” [by Jesse Stone], and “Tutti Frutti” [by Little Richard and Dorothy LaBostrie]) and because many people thought Presley sounded black, this popular album was instrumental in bringing black music, such as that written by McCoy, to white listeners, and especially to teenagers, many of whom responded to it as an antidote to and liberation from the largely insipid music to which they were exposed on white radio stations and, increasingly, television, such as that performed on Your Hit Parade. Presley also recorded McCoy’s “I Beg of You” (1957), written with Kelly Owens.

In her native Arkansas, Marie Hinton absorbed the blues, committed herself to music upon hearing the International Sweethearts of Rhythm while in high school, and added Rose to her name at eighteen. After working for a family in the Catskill Mountains during the summer of 1942, she moved to New York City, where she held menial jobs (housecleaning, ironing shirts at a Chinese laundry) and began singing in small clubs. The next year she married James McCoy. Her first composition to be recorded was “After All,” by the Dixieaires in the mid 1940s. She recorded for the initial time in 1952 (“Cheating Blues” and “Georgia Boy Blues,” both of which she wrote). Soon thereafter, she and Charlie Singleton formed a songwriting team, the success of which led to her becoming wealthy enough to buy a house (in Teaneck, NJ), a Cadillac, and a yacht; her husband bought a nightclub. Soon, though, she became financially overextended to the degree that she almost lost her home. Because around this time the demand for songwriters began to decline (following the lead of such singer-writers as Chuck Berry, Fats Domino, and Little Richard, an increasing number of vocalists started performing their own material), she made money writing jingles, producing recording sessions, and managing the singer Craig Hansford. The last significant performer to record a new McCoy composition was Shirley Caesar in 1977 (“How Many Will Be Remembered”). McCoy’s later creations constitute a career denouement.

McCoy was fortunate to have had Corsano as a friend. When they met at a party in 2001, they discovered that they lived within ten minutes of each other; soon, Corsano drove McCoy places, became captivated by stories the composer told, and in time decided to document the career of this accomplished woman who was not widely known. Corsano’s ultimate goal was political: to encourage the Songwriters Hall of Fame to induct McCoy into its organization.

In her book, Corsano is primarily interested in McCoy’s songs and recordings of them, though she is not particularly concerned about what makes the compositions appealing. She emphasizes her focus on compositions by titling each chapter (chapters are unnumbered) with the name of one of McCoy’s tunes. For example, “I’ll Be All Right” (recorded in 1956 by Little Jimmy Scott, one of McCoy’s favorite singers) is the title of the chapter about the breakup of the McCoy-Singleton partnership. Yet this chapter is less about the song or even McCoy or Singleton than about collateral issues. Here is its structure: Corsano explains why McCoy wrote the piece, identifies singers who recorded it (Scott and Joe Medlin), specifies other McCoy-Singleton songs that Scott sang, names numerous jazz musicians who recorded for the label that recorded him (Savoy), notes that McCoy and Scott performed at the same New Jersey club, indicates that others also admired him, says that he recorded for Ray Charles’s Tangerine label, notes that he was the subject of a film documentary, and concludes by saying that McCoy had collaborators after Singleton. That is, the chapter is mostly about Scott and incidentals. The only insight the author offers about the song is that McCoy wrote it to express a feeling that attends the end of a romantic relationship, even though her association with Singleton was professional and platonic. Other chapters similarly keep McCoy in the background.

Yet in her narrative Corsano often permits McCoy’s voice to dominate. For example, “Hey Look World,” “If I Had Any Sense (I’d Go Back Home),” and “My Personal Possession” are among the chapters containing more of the composer’s words than the author’s. When, where, and to whom did McCoy speak, and how were her words recorded? The author does not say. Though quoting one’s subject can be valuable, doing so excessively is often irritating, as is the case in this book. The author would have been well advised to assimilate the information the composer provided and incorporate it, when appropriate, into her story in her own words, acknowledging McCoy when necessary and quoting her only to emphasize a point or add flavor to the text.

Though I am in no position to challenge McCoy’s assertions, the author seems to accept them all without question, even when some invite skepticism. McCoy tells of fighting a female pianist, a nightclub patron, and the composer Dorian Burton. Is she credible? Does Corsano believe that McCoy held the hand of nervous Savannah Churchill when the latter recorded McCoy’s “Last Night I Cried over You”? That McCoy did not know the words to “Mambo Baby” when singing it with Lionel Hampton? That someone stole bolts from McCoy’s yacht? That an executive of Commonwealth United, an entertainment company, was so moved by McCoy’s rendering of a song that he cried? That James Brown made his brass players practice so much that their lips bled? Perhaps all these claims are accurate. Without confirmation, how is one to know?

Corsano deals primarily with McCoy’s professional life, which, given her goal, is appropriate. Yet she avoids asking questions that arise from personal information she provides about McCoy. This is especially the case with issues relating to the composer’s marriage, which endured from the couple’s 1943 nuptials until James McCoy’s death in 2000. Because the author establishes Rose Marie’s dedication to James (desiring to be with him, Rose Marie declined an offer to tour with Big Maybelle), one wishes to know how she responded to his leaving her several times in order to live with other women. In mentioning but not identifying Rose Marie’s “personal heartache” (153), does the author allude to James’s waywardness? She does not say. Further, Corsano states that “it’s not likely [Rose Marie] spent all those years [when James deserted her] alone” (171). Did she have lovers? Corsano does not say. During one of Rose Marie’s brief periods on the road while the couple lived together, James bought Mitzi’s Cocktail Lounge in Passaic, NJ. This impetuous purchase led to serious financial difficulties that caused Rose Marie to cover expenses by borrowing money, yet she stood by him, as she always did, including when, late in life, he developed Alzheimer’s disease. She tended to him until his death. Explaining her dedication to this philandering, financially naive man by saying only that “no one could replace James” (171) is inadequate. Might Rose Marie have had reasons for devoting herself to him? The author does not say.

The shortcomings mentioned here lessen the value of Corsano’s book. Yet the author correctly identified McCoy as a worthy subject and surely wrote the composer’s story to the best of her ability. She succeeded to the degree that the book will appeal to readers interested in female songwriters or rhythm and blues. Especially because she published it herself, her dedication to McCoy—in time, in money–merits praise. Whether the book will lead to McCoy’s being enshrined in the Songwriters Hall of Fame remains to be seen.

Author = Benjamin Franklin V

Authors = Kyla Titus and Chica Boswell Minnerly=The Boswell Legacy: The Story of the Boswell Sisters of New Orleans and the New Music They Gave to the World

Publisher = Vet Boswell Family Collection

Review =

In the opinion of Will Friedwald, the Boswell Sisters–Martha (1905-1958), Connie (1907-1976), and Helvetia (Vet) (1911-1988)–are “the greatest of all jazz vocal groups” (Jazz Singing: America’s Great Voices from Bessie Smith to Bebop and Beyond [New York: Scribner’s, 1990], 156). Though designating anything that lacks an objective standard of measure as “the greatest” mainly indicates personal preference, Friedwald, who is as knowledgeable about jazz singers as anyone, gives good reasons for his opinion. He is not alone in valuing the sisters’ music. According to the Encyclopædia Britannica, the trio ranks with Lambert, Hendricks, and Ross (established in 1957) as “the two greatest jazz vocal groups of all time” (http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/764573/the-Boswell-Sisters; accessed 30 November 2014). In other words, the Boswells are highly regarded by the cognoscenti. They are also largely unknown by more general music lovers, despite efforts by the Pfister Sisters (who are not siblings) and a few other groups to perpetuate their kind of music, as well as the holding of the Boswell Sisters Centennial Celebration in their hometown of New Orleans in 2007 (when Connie would have turned one hundred) and a weekend celebration sponsored by the Historic New Orleans Collection in October 2014. The second of these tributes was organized by Kyla Titus.

In order to draw attention to the sisters, Titus wrote The Boswell Legacy. Its title page identifies the authors as Titus and Chica Boswell Minnerly. Titus graciously acknowledges Minnerly, her mother and the daughter of Vet Boswell, because in 1989 Minnerly and David W. McCain started writing a text that, after they abandoned it, ultimately evolved into The Boswell Legacy, thanks to Titus’s efforts. McCain wrote the introduction to the book. Minnerly also maintained a Boswell archive, the source of much if not most of the information Titus presents.

Titus’s seemingly authoritative account of the sisters’ lives and careers may be summarized as follows. Because the siblings grew up in the same household and lived and traveled together even when they were most popular, their biographies are similar until the mid 1930s, when the Boswell Sisters disbanded. Musically precocious (as was their brother Clydie, born in 1900, who died of influenza during the 1918 pandemic), they had private music lessons (classical) and, by the late 1910s, performed locally as instrumentalists. Martha played piano; Connie, saxophone and cello; Vet, banjo, guitar, and violin. They discovered syncopation and soon used it in their playing. They might have been susceptible to it because their father, A. C., a former showman, was familiar with black music and could play ragtime piano. Jazz cornetist Emmett Hardy became their friend and inspired them. They attended numerous musical performances, including at the Lyric Theatre, which featured such black singers as Bessie Smith and Mamie Smith, who became major influences, especially on Connie. By the mid 1920s, they added singing to their act; reaction to it caused them to forsake their instruments and become a vocal group, though Martha served as accompanist. They recorded for the initial time when they were nineteen, seventeen, and thirteen, respectively. The Boswell Sisters’s existence was threatened when Martha married in 1925 and gave birth to a son the next year; the crisis was averted when Martha continued practicing with her siblings, she soon divorced her husband, and family members tended to the child. The group toured on the vaudeville circuit, appeared in movies, performed regularly on radio, and recorded frequently. Problems arose in 1930 when Harry Leedy, who was enamored of Connie, succeeded Martha as the sisters’ manager and began promoting Connie more than the Boswell Sisters. Nonetheless, he managed the siblings during their most productive and rewarding years. Their fame was such that they had an audience with President Hoover, twice toured Europe, and made more movies. They broke up soon after a recording session in early 1936. This happened primarily because Connie wanted a solo career (which proved successful), though she attributed the demise to her sisters’ domestic realities. By then, all three women were married: the families lived in Toronto (Martha), rural New York (Vet), and New York City (Connie, who married Leedy). Titus concludes her book by briefly summarizing the siblings’ post-group lives.

Titus clarifies two matters relating to Connie that have not been fully understood: the cause(s) of her paralysis and why the spelling of her given name changed. At age three, she was injured in a wagon accident and later had polio; as a result of these events, but apparently mostly because of the second, her legs were paralyzed, though she lost all ability to walk only after falling from a window at age twenty-two. This infirmity explains why she performed seated. It also accounts for her developing considerable upper-body strength, as may be observed in a photograph of her, around age eight, hanging by one hand from a ledge of the family’s house. (The text is enhanced by many photographs.) Connie quit dotting the “i” in her name in order to save time when signing autographs circa 1942; the spelling therefore appeared to be Connee, by which she became known. The modification was, in a sense, accidental.

Despite the thoroughness of her book, Titus introduces some topics for which she provides insufficient information. For example, she demonstrates that for a long time Connie and Leedy had strong feelings for each other. Because Connie lived with her sisters during this period yet was in frequent professional contact with Leedy, one would like to know the nature of the couple’s personal relationship and how it worked logistically, since she could move about by herself only in a wheelchair. Perhaps Titus does not address the romance because it is not documented. If so, her refusal to speculate is admirable. When writing about a 1955 photograph of the siblings, the author states that by then the lives of Martha and Vet were “isolated and lonely” (8), but does not substantiate the claim, especially about Vet. Further, she mentions “a bitter legal fight over [Martha’s] estate” (180) without providing particulars, such as the issues or parties involved in it.

Though Titus’s prose is adequate, she uses words that do not allow for exception when there are exceptions, as in the constructions “the two sisters went everywhere together” (18) and “she and her mother were constantly at odds” (36). She suffers a lapse such as this: “Jimmy Fazio . . . knew whom they were” (9). She uses clichés, including “the families heard the call of the west” (14) and “his worldly charm” (15). A copy editor would have caught the infelicities, but Titus, who probably paid for the publication of the book, cannot be blamed for not having one: copy editors are expensive. These and other prose shortcomings do not lessen the value of The Boswell Legacy.

Immediately before the epilogue, Titus refers to the gloriousness of the siblings’ creations and asks readers to “listen to the music and see if [they] do not agree” with her assessment of it (186). This is good advice because Titus discusses the music so little that one cannot conclude much about it from her text and therefore cannot comprehend why it was so popular. In only a few instances does she characterize the group’s sound: “in the trio’s arrangements, the sisters always made space for the musicians to play solo spots, with room to do their own thing without interference. They were masters of improvisation—the cornerstone of jazz” (112); “they received hundreds of requests for their arrangements, which, aside from their exceptional timing and voice blend, were central to the ‘Boswell Sound’” (117); and “they were close harmony singers and needed to keep the sound soft and intimate” (120), which is why they used a microphone during live performances. (“Between the Devil and the Deep Blue Sea,” “Got the South in My Soul,” and other tunes disprove the author’s statement that all the siblings’ recordings feature instrumental solos.) She notes that the sisters created their arrangements by working backward from the end of a chorus. Observations about their music in quotations from two published sources are more substantial than Titus’s own: in a 1937 number of Billboard, a writer claims that the siblings introduced variations on the first chorus in the second one, a technique many popular singers soon adopted; in an article published in 2008, James Von Schilling focuses on the sisters’ performance of “Crazy People” in the 1932 movie The Big Broadcast, though his commentary is descriptive, not analytical. While the book’s subtitle indicates that Titus will tell “the story of . . . the new music [the siblings] gave to the world,” she does not do so effectively. A few substantial paragraphs or a brief chapter about the quality of the sisters’ music would have been helpful in this regard.

Though Titus specifies improvisation (by the likes of Bunny Berigan, the Dorsey brothers, Benny Goodman, Manny Klein, and Joe Venuti) and close harmony (probably absorbed while growing up in a family that featured barbershop quartet singing by the parents and an aunt and uncle) as hallmarks of the sisters’ music, she overlooks the Boswells’ energy, which helped elevate their creations above the mostly staid popular music of the time. (Among contemporaneous vocal groups, probably only the Mills Brothers came close to the siblings’ inventiveness and musical accomplishment.) Further, the sisters’ music is distinguished by an appealing irregularity of tempos, keys, and accents.

Fortunately, readers interested in the Boswells’ music can easily honor Titus’s request to listen to it by accessing it—and viewing some of the trio’s movie appearances–at youtube.com. There, one special treat is a scratchy recording of “I’m Gonna Cry,” from the sisters’ initial recording session (1925). It is a feature for Connie, whose singing seems derived from blues singers she heard as a youth. She had a large, powerful voice—though less so than Bessie Smith’s, for example–which is evident here as she belts out the song. During a chorus, she sings in the manner of an instrument, with Vet providing harmony. Someone listening to this performance unaware might well think Connie black and confuse her with one of the classic blues singers. One would likely be surprised to learn that at the time of this recording, she was only seventeen.

Though in time the sisters’ singing became less coarse than on “I’m Gonna Cry,” it remained adventuresome and dynamic. Partly because of Connie’s retention of a blues feeling as well as her spontaneity and use of jazz phrasing, the group not only became popular, but influential. The siblings directly inspired the slicker and less improvisational Andrews Sisters, who became possibly even more popular than the Boswells had been. Perhaps most importantly, Ella Fitzgerald admitted to only one musical influence, Connie, who, according to Norman David, “fused the blues nuances of Bessie Smith’s singing and the jazz vocabulary of the genius [Louis] Armstrong to create her own unique style.” He also believes that Fitzgerald learned, from Connie, how to meld “the jazz idiom with popular music” (The Ella Fitzgerald Companion [Westport, CT: Praeger, 2004], 40). That is, Connie’s singing with her sisters was the greatest influence on the single most accomplished female jazz and pop singer. Inexplicably, Titus omits Fitzgerald from her text, though she mentions her on the back cover, where she states, without comment, that Fitzgerald “consistently credited Connie Boswell as her main influence.”

In sum, Titus has written a valuable book. Because it is based on archival research, it is the most reliable source of information about the sisters’ lives and careers. Though the author largely ignores the nature of the siblings’ music, readers can enjoy and evaluate it by accessing it on-line. Reading her study in conjunction with listening to the music will lead to an understanding of the sisters’ innovations and of why the group was so popular and influential. The recordings of the Boswell Sisters are of lasting value, as is The Boswell Legacy.

Author = Benjamin Franklin V

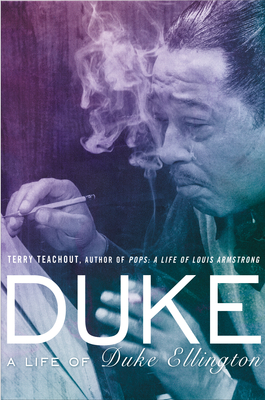

Author = Terry Teachout

Genre = Jazz

Title = Duke: A Life of Duke Ellington

Publisher = Gotham Books

Review =

Duke Ellington is arguably the most important person in jazz history. Without question the major jazz composer, he would almost certainly be enshrined in any pantheon of American composers. He led a band from the 1920s until 1974, the year he died, partly so he could hear his creations played by superior players, whose individuality inspired him to write tunes with them in mind, such as “Concerto for Cootie” for trumpeter Cootie Williams. If he did not always acknowledge their contributions to compositions credited only to him, he paid them well and abided their idiosyncrasies and indiscretions to the degree that his major players stayed with him for decades. Harry Carney, for example, was the baritone saxophonist from 1927 until after the leader’s death. When a star soloist resigned, it was news, as when Williams departed for Benny Goodman’s group in 1940: the jazz press noted it, and Raymond Scott even wrote a tune titled “When Cootie Left the Duke.” In time the defectors, including Williams, returned, partly because they were unsuccessful away from the band, partly because of the security Ellington offered, and partly because he provided a context for them to perform to best advantage. He worked tirelessly, distracted from music seemingly only by sex, for which he would walk, as he once said, past money to attain. Even though he accurately presented himself as dignified and sophisticated--cultured, refined, and elegant--so he and by extension his music would reflect well on his race, he was impenetrable. He kept people at charm’s length, seldom revealing much about himself, even in Music Is My Mistress, his 1973 autobiography. In Duke, Terry Teachout concludes that “everyone knows him—yet no one knows him. That was the way he wanted it” (361).

Ellington might have been inscrutable, but Teachout’s admirable narrative conveys much of what is known about him, though most of the information, by far, concerns his professional life, as it should. While interesting, his little-known personal life—the never-divorced wife who once slashed his face; the discarded lovers who married his sidemen, including trombonist Lawrence Brown—is mostly irrelevant to what makes him important: his music. On this topic, the author is compelling. Though he details aspects of numerous recordings (recordings constitute the proof of Ellington’s greatness), he does not mention every session, or every tune from the sessions he does discuss. Mainly, he treats highlights. When focusing on “Ko-Ko” (1940), for example, he comments on the opening riff and the dissonant piano in the fourth chorus before concluding that this performance is “a relentless procession of musical events that contains not a wasted gesture. Every bar surges inexorably toward the final catastrophe, after which no response is possible but awed silence.” He terms this “the greatest of Ellington’s three-minute masterpieces” (208). As this statement indicates, he has beliefs--and provides reasons for them. Generally, though, he agrees with the critical consensus, as when valuing most highly the band that was active circa 1940, the one now known as the Blanton-Webster band for two of the most important sidemen, bassist Jimmy Blanton and tenor saxophonist Ben Webster. Agreement with the majority view is inevitable because Ellington has been taken seriously for a long time and has been written about voluminously. Men of strong opinions, James Lincoln Collier and Gunther Schuller are just two of the writers who have addressed Ellington and influenced opinion about him. Further, the music speaks for itself: The qualitative difference is obvious between such early classics as “Creole Love Call” (1927) and “The Mooche” (1928) and such late albums as Paris Blues (1961) and Hits of the 60’s This Time by Ellington, which is also known as Ellington 65 (1964). To his book, Teachout appends a list of fifty key recordings arranged chronologically, though he does not indicate what he means by “key.” Does he mean that these recordings are, to him, Ellington’s best? The most important in the development of the leader’s career? Something else? No matter what he means, he intends to commend them. In doing so, he provides guidance to readers unfamiliar with Ellington’s music; the list will also possibly inspire debate among initiates who will doubtless agree that most of the recordings the author mentions are significant. Most of the recordings, but not all of them: I, for one, do not value the 1968 Second Sacred Concert. I also think the album Money Jungle (1962) is effective as a whole, not just for “Fleurette Africaine.”

Despite being unable to detail much personal information about the adult Ellington, Teachout treats his relationships with professional associates, including two who operated largely behind the scenes: his manager and major collaborator. He explains Irving Mills’s importance by demonstrating how the manager helped establish the leader’s image and promoted Ellington by, among other things, getting him good bookings and arranging for the band to appear in movies. Teachout also explains why Mills is identified as co-composer of tunes written by his employer, such as “Mood Indigo.”

Though some members of the Ellington organization despised the leader (Lawrence Brown is one who did), others idolized him. Paramount among the latter group was composer and pianist Billy Strayhorn, who auditioned for Ellington in late 1938 by playing two Ellington tunes plus two of his own compositions, “Lush Life” (written at eighteen) and “Something to Live For.” Ellington soon hired him. Strayhorn wrote numerous pieces for the band, including “Take the A Train,” which became its theme, and “Chelsea Bridge”; he collaborated on others, such as “Rocks in My Bed.” In time resenting Ellington’s paternalism and co-opting of his compositions, Strayhorn left his mentor in the early 1950s and began writing on his own. Later, the relationship was renewed; they collaborated on the suite Such Sweet Thunder (1957) and the popularly successful The Nutcracker Suite (1960). Despite their differences, Ellington was devastated by his associate’s death (1967). Distraught, he thought himself incapable of delivering the elegy he wrote, so he “sat in stony silence as his heartfelt words were read out loud to the mourners” (334). Soon thereafter, Ellington recorded an album (. . . And His Mother Called Him Bill) devoted to Strayhorn’s compositions. On it, he plays “Lotus Blossom” so movingly that it stands as one of the most emotional performances of his long career.

Teachout makes many astute observations. One concerns how Ellington’s compositions differ from those of all other big-band leaders: “instrumental color” (213). Another explains how Ellington attained this coloring: while arrangements performed by other bands kept the various sections (trumpet, trombone, woodwind) separate, Ellington “mixed the sections of his band together” (213). The author also observes that Ellington was not a natural melodist and that he could not grasp the necessity of writing musicals that are driven by the songs. Jump for Joy is an example of this failure. He explains how Ellington deftly solved problems caused by the 1941 creation of Broadcast Music Incorporated to compete in the licensing of songs with the established American Society of Composers and Publishers. (Ellington was a member of ASCAP.) Additionally, he gives some inside information about Ellington’s musicians: the hiring of Rex Stewart angered Cootie Williams, Barney Bigard was a prankster, and Tricky Sam Nanton was an intellectual. He explains why Ellington valued the valve trombone, and notes that he wore a girdle.

In addition to providing a comprehensive view of Ellington and his music, Duke is well written and easy to read, even by those unfamiliar with musical terminology and who cannot read music. “Ostinato” (162) is probably the most demanding musical term Teachout uses; nowhere is there musical notation. He explains the method he used when writing the book: It “is not so much a work of scholarship as an act of synthesis, a narrative biography that is substantially based on the work of academic scholars and other researchers” (363), though he acknowledges his responsibility for interpreting this material. His indebtedness to the work of others is evident in eighty pages of notes, so anyone wishing to confirm the author’s statements may do so. A reader may easily evaluate Teachout’s interpretations of Ellington’s music by accessing much of it on youtube.com, and for this reason I recommend reading the book while seated near a computer. Want to hear Bing Crosby singing “St. Louis Blues” (1932) with Ellington? It is on YouTube, as is “Old Man Blues” (1930), of which Teachout makes much. What about Ellington’s presence on film? The obscure Symphony in Black (1934) is there, as are two movies from 1937, The Hit Parade and Record Making with Duke Ellington and His Orchestra.

Teachout concludes his narrative perfectly. Returning to the impossibility of knowing many facts about Ellington, the author notes that Ellington actually revealed himself: “He left behind his music, the only mistress to whom he told everything and was always true” (361).

Author = Benjamin Franklin V

Date = 25 February 2014

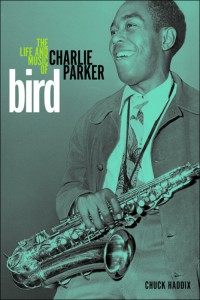

Author = Chuck Haddix

Genre = Jazz

Title = Bird: The Life and Music of Charlie Parker

Publisher = University of Illinois Press

Review=

Charlie Parker (1920-1955) is among the most documented jazz musicians. During a relatively brief recording career (1940-1954), he participated in approximately 250 recording sessions, around 175 as leader. He has been written about extensively, including in books by people with first-hand knowledge of him (such as Ross Russell) and by major critics (such as Gary Giddins). Several Parker discographies have been published. Carl Woideck compiled a collection of writings about him; Ken Vail chronicled his life. Mark Miller detailed his time in Canada. Even a book reproducing his memorabilia has been published. The list goes on. Chuck Haddix’s Bird is one of the most recent books to focus on Parker.

Now, almost sixty years after Parker’s death, a writer needs to have significant new information about—or a fresh approach to--the musician before undertaking a book about him. Because of the author’s research in census records, city directories, and other documents, Bird provides new information, especially about Parker’s early years. All knowledge is good, but the facts Haddix discovered are mostly trivial.

Here are some facts Haddix provides, all of which are new to me. Commenting on the Hannibal Bridge, he notes that “in 1917, at the peak of rail traffic, 271 trains passed daily through Union Station, the massive stone Beaux Arts train station located on the southern edge of downtown” Kansas City, Missouri (7). He records that “as a teenager” in Oklahoma, Parker’s mother “worked as a maid for a household of six headed by Mary H. Morris on Main Street in McAlester, the county seat” (7), and that Parker’s father, “born in 1886,” resided “in a rooming house at 311 West Sixth Street in the heart of a crowded slum on the northern rim of downtown Kansas City, Missouri” (7-8). He observes that Parker played in the band at the 1935 high school graduation of Rebecca Ruffin, who married him the next year; the band performed Elgar’s “Pomp and Circumstance” and the first theme from Coleridge-Taylor’s “An Imaginary Belle” (17). (Does Haddix mean “Scenes from an Imaginary Ballet”?) He pinpoints the location of Musser’s Ozark Tavern, where, in 1936, Parker was en route to play when he was injured in an automobile accident that killed a companion: “three miles south of Eldon, Missouri, at the junction of Highways 52 and 54” (24). Haddix provides numerous addresses, such as those for Kansas City Musicians’ Local 627 (18) and Lucille’s Paradise (28), the Kansas City club where Parker joined the band of Buster Smith.

As the book progresses, the author presents less new information and increasingly treats familiar Parker material: humiliation by Jo Jones, discovering how to create music he had been hearing in his mind by playing “Cherokee” in a new way, various band affiliations, how he became known as Yardbird (later shortened to Bird), the Benzedrine episode with Rubberlegs Williams, the engagement at Billy Berg’s, confinement at Camarillo State Hospital, recording sessions, relationships with wives and Chan Richardson, death in Hotel Stanhope, and so forth. Though he interviewed people who knew Parker, including Jay McShann, Haddix based his treatments of events mainly on secondary sources, such as Robert George Reisner’s Bird: The Legend of Charlie Parker (1962), which includes various people’s recollections of Parker, and Mark Miller’s Cool Blues (1989).

When presenting information from secondary sources, Haddix sometimes seems credulous, as when recounting Parker’s conversation with Einstein (62-63), sleeping under the bandstand during a performance by the Earl Hines band (64), and sleeping all day in a telephone booth (71). These things might have happened, though in each instance Haddix relies on a single source: first, Junior Williams; second, Billy Eckstine (when citing the source of Eckstine’s quotation, Haddix records the wrong page number at n. 12 on 171; Eckstine’s words are from Reisner’s Bird, 85, not 17); third, Art Blakey. Providing another source for each would have bolstered the author’s claims.

Because the sub-title implies full treatment of Parker’s life and music, it misleads: Bird is primarily biographical. When discussing music, Haddix mostly treats externals, as the following illustrates. For Savoy Records, Parker led his first commercial session on 26 November 1945. Haddix notes that Parker composed tunes for it, addresses the confusion over which pianist (Argonne Thornton or Dizzy Gillespie) and trumpeter (Gillespie or Miles Davis) perform on which selections, states that Parker had horn problems, identifies the number of takes for each tune, believes that Parker undermined the session by approaching it haphazardly, and points out that reviewers praised Parker’s solos while “panning the overall result” (83). The author offers what passes for analysis when commenting on “Now’s the Time,” noting only that Gillespie’s altered chords caused Davis to play “out of key” (82), though he does not demonstrate cause and effect. Haddix thinks that this recording highlights “Charlie’s Kansas City roots and deep feeling for the blues” (82), but without explaining how.

Though I acknowledge the difficulty of conveying, in prose, the nature of music, Haddix’s characterization of Parker’s gives little if any sense of its gloriousness—and it is this quality that makes the saxophonist’s life worth documenting. Haddix does not even mention that Parker’s solo on “Ko Ko” (from the “Now’s the Time” session) is widely considered one of the most impressive and important solos in jazz history. It is so highly regarded that it was in the first group of recordings selected for the National Recording Registry at the Library of Congress (see item 36 at http://www.loc.gov/rr/record/nrpb/registry/nrpb-2002reg.html; accessed 24 February 2014). The Library of Congress justifies its inclusion by stating that it “signaled the birth of a new era in jazz—bebop.” Though the accuracy of this claim can be debated, Haddix ignores the recording’s significance. To him, it is just another Parker recording. He also fails to indicate that two of the tunes Parker wrote on the spur of the moment for this session—“Billie’s Bounce” and “Now’s the Time”--are so appealing that each has been recorded hundreds of times. They are part of the jazz repertoire, as anyone who has listened to much jazz can attest. (Ted Gioia identifies them as such in The Jazz Standards [2012].) “Billie’s Bounce” was inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame (2002). In other words, Haddix does not attempt to do justice to Parker’s music.

This book needed copy editing. For example, Haddix writes “fed up towing the Jim Crow line” (69; the correct word is “toeing”) and “he was getting ringing wet” (72; “wringing”). Because he quotes the latter correctly from a published source, “[sic]” should have been inserted after “ringing” to indicate awareness—if there was awareness--of the error in the source material, an interview with trombonist Trummy Young. Singer Ethel Waters is identified as Ethyl (77). Haddix twice states that the Kansas City Call was an African American newspaper (17, 28) and four times notes that Emry Byrd was known as Moose the Mooche (86, 95, 146, 184). The given name of John S. Wilson is misspelled (171, n. 29). No publication date is provided for Chan Parker’s My Life in E-Flat (172, n. 41). The index identifies the radio program Bands for Bonds as Bands for Bond and alphabetizes Ross Russell according to his given name. Though relatively unimportant, these and other infelicities should not occur in a book published by a major university press.

Well-written and generally accurate, Bird will benefit readers who desire an overview of the musician’s life and career. Those already familiar with Parker will learn from it primarily specifics about his early years, such as addresses of various places. It is not the book to consult for significant new biographical information or for a discussion of or insight into his music.

Author = Benjamin Franklin V

Date = 24 Nov 2013

Date = 24 Nov 2013

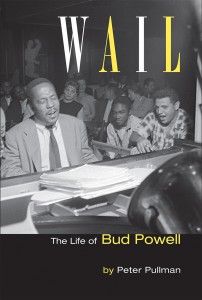

Author’s Name = Peter Pullman

Genre = Jazz

Title = Wail: The Life of Bud Powell

Publisher = Peter Pullman

Review=

Because Peter Pullman began researching Bud Powell in the early 1990s, he probably knows more about the pianist than anybody, including Guthrie P. Ramsey, Jr., whose recent The Amazing Bud Powell uses Powell primarily as a springboard for musing about genius and the social identity of bebop. Pullman’s knowledge is confirmed by his study of the pianist, an almost 500-page book published in 2012 at the author’s expense. For it, Pullman conducted approximately 800 interviews, listened to all of Powell’s recordings, and consulted seemingly everything relating to his subject. After assimilating this information, he wrote a balanced biography that details highlights as well as unpleasantnesses, of which there were many. He treats his subject’s youth, professional associations, recordings, performances, involvement with women (mostly platonic), alcoholism, occasional heroin use, musical decline, revered status in France, and more. Though Pullman is given to overstatement, a measured tone enhances his narrative, as may be observed when he details the two known times that Powell struck his mother (210, 223). He does so dispassionately, refusing to milk the events for pathos, as some writers might have done.

A schooled pianist influenced by the likes of Bach, Ravel, and Art Tatum, Powell (1924-1966) joined the band of his brother William in 1940, played in his native Harlem at Minton’s Play House and Monroe’s Uptown House when bebop was being developed there, and joined the Sunset Royals before entering the big time with Cootie Williams in 1942. Also with Williams irregularly during this period was Charlie Parker, whose new approach to music Powell embraced. His life changed in 1945, when he was reportedly beaten by police after being arrested for drunkenness. The resulting headaches and strange behavior led to hospitalization and to a diagnosis of manic depressive psychosis. Thus began serious emotional problems that lasted for the remainder of his life.

Yet off and on for approximately a decade beginning in 1947, Powell led impressive trio sessions for such labels as Roost, Clef/Norgran/Verve, Blue Note, Debut, and RCA. His bassists included Ray Brown, Paul Chambers, George Duvivier, Percy Heath, and Curly Russell; Art Blakey, Kenny Clarke, Roy Haynes, Buddy Rich, and Max Roach were among his drummers. An album of Powell’s solo performances was recorded in 1951. Powell’s reputation rests primarily on music from these sessions. From the beginning of his career, however, leaders recognized the pianist’s ability, as the many impressive recordings on which he appeared as sideman illustrate. These include Cootie Williams’s “Round Midnight” (1944), Dexter Gordon’s “Long Tall Dexter” (1945), Sarah Vaughan’s “If You Could See Me Now” (1946), J. J. Johnson’s “Jay Bird” (1946), Fats Navarro’s “Boppin’ a Riff” (1946), Charlie Parker’s “Donna Lee” (1947), Sonny Stitt’s “All God’s Chillun Got Rhythm” (1949), Quintet of the Year’s “Wee” (1953), Coleman Hawkins’s “All the Things You Are” (1960), Oscar Pettiford’s “Blues in the Closet” (1960), Charles Mingus’s “I’ll Remember April” (1960), Don Byas’s “I Remember Clifford” (1963), and Dizzy Gillespie’s “Groovin’ High” (1963). Among the most significant musicians in jazz history, these leaders could have used any available pianist they desired, but they chose Powell. Why? Because of his inventiveness and his expressive, intense style, qualities that made him the preeminent bebop pianist and make his most accomplished music enduring. Still, his recordings and live performances were hardly consistent, and his life was erratic. In Wail, Pullman provides all the details of Powell’s life and career that most people would wish to know, but is most impressive and valuable when discussing the problems that led to the pianist’s decline--mainly his emotional problems, which led to hospitalizations. Pullman had access to medical records, some willingly provided by institutions, but others relinquished only after he won the suit he filed against the New York State Office of Mental Health in the New York Supreme Court. As a result, he bases his comments on the best possible evidence.

That Powell was emotionally unstable is not news; fortunately, Pullman provides many details about this instability that were not previously known. From the medical records he learned, for example, about the pianist’s difficulty with what psychiatrists call ideas of reference (considering ordinary events as of great personal significance). In 1947, drinking exacerbated this problem to the degree that in a club Powell fought a patron over the issue of race, an action that led to his confinement in the state hospital in Creedmoor, NY. Because of his disruptive behavior while still there the next year, he was forced to wear a straightjacket; then, he underwent two series of electroconvulsive therapy (shock treatments). On the topic of the pianist’s emotional state, Pullman notes that Powell was predisposed to a nervous breakdown; he also believes that Powell was disserved by judges who committed him to psychiatric hospitals and that the pianist received inadequate screening during the admission processes. I find his treatment of Powell’s emotional problems sound (I am neither a psychiatrist nor a mental health professional), though I wonder if some of his judgments of medical personnel are too harsh.

Powell’s greatest recordings (including “All God’s Chillun Got Rhythm,” “Parisian Thoroughfare,” and “Un Poco Loco”) rank with the best work of any jazz pianist, which makes Powell’s artistic decline all the sadder. Pullman notes that it began in 1953, the year Powell performed at Massey Hall in Toronto with his trio and with a quintet featuring Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie. (Pullman believes that Powell’s solo on “Salt Peanuts” with the quintet “ranks with his greatest, regardless of context” [185]). The author identifies strong and weak performances from then until the end of the pianist’s career. At his last recording session, as leader in January 1966, Powell played so poorly that Pullman concludes that none of the music “should have been considered for release,” though the session was released, on Mainstream. He further states that the music on this album constitutes Powell’s “last, embarrassing attempt . . . to make music” (376). While I agree, to this statement I would add “sad” between the first two words.

As an examination of Powell’s life—professional and personal--Wail will probably never be surpassed, which is not to say it is perfect. (What is?) Pullman makes claims he cannot support (“Powell gave his performances every drop of sweat that he had” [150]); treats George Shearing contemptuously (152, 183); states what people thought when he has no way of knowing (“Powell had to be thinking of the long, lonely voyage back to New York” [208]); criticizes Powell’s fan Evelyn Glidden gratuitously (237); dismisses people with a single unflattering adjective (“the pedantic Kurt Mohr” [290], “the bourgeois Paudras” [337]); fails to define terms (October Revolution [358, 372]); and treats Leonard Feather’s Blindfold Test unfairly (382). He also seems credulous, as when believing that Thelonious Monk cried because of his supposed pianistic inferiority to Powell (303) and that Powell recited the Gettysburg Address from memory when asked to do so (420). In all likelihood, a copy-editor would have challenged Pullman on some of these points and made stylistic suggestions, such as eliminating “, though,” in most instances. Granted, Pullman published the book himself, so the cost of engaging a copy-editor for his long manuscript probably would have been prohibitive. Ultimately, these and other infelicities are relatively insignificant in the context of the book’s strengths, especially its comprehensiveness and detail.

Had Powell not been a gifted person, his life would hardly warrant comment. Yet because he was an accomplished pianist, it assumes importance. Thus, Pullman’s book is well worth reading by anyone interested in jazz, the creative process, or emotionally impaired artists. Though one would gain a full sense of Powell from it, it might best be read in conjunction with listening to his recordings, most of which are readily available. (A Powell discography would have enhanced the book.) Doing so would permit one to hear his greatness (and not-so-greatness) and understand why Pullman evaluates the pianist’s artistry as he does.

Author=Benjamin Franklin V

Author Name = Paul de Barros

Genre = Jazz

Title = Shall We Play That One Together? The Life and Art of Jazz Piano Legend Marian McPartland

Publisher = St. Martin’s Press (2012)

One of the most famous jazz musicians, Marian McPartland is known less for her playing than for hosting the weekly NPR program Piano Jazz for more than three decades, beginning in 1978. Initially, each program featured McPartland and another pianist: the two performed selections together, but also solo. In time, the concept expanded to include guests other than pianists. The program was successful for several reasons, including McPartland’s engaging personality, articulateness, and British accent; the host and guests’ intelligent discussions; the quality of the music; and the hour-long format, which permitted the participants time to talk and play without rushing. Some of the shows were released on CD, and the show continues being broadcast in re-runs. For the title of his biography of McPartland, Paul de Barros borrowed a question the pianist often asked on her program.

Yet McPartland was a substantial pianist. (Though she is living, I use the past tense because she no longer plays.) Classically trained, she became enamored of and proficient in jazz, ultimately comfortable performing in traditional, modern, and even free modes. To me, her most rewarding decade was the 1950s, when she led a group with bassist Bill Crow and drummer Joe Morello, had a multi-year engagement at the Hickory House in New York, and recorded three appealing albums for Capitol in successive years, the first in 1954: At the Hickory House, After Dark, and The Marian McPartland Trio. (I am unfamiliar with her fourth Capitol album, With You in Mind [1957], which de Barros deems “bland” [178]). That decade, she matured as a musician by becoming harmonically sophisticated and apparently gaining confidence in her artistry, even though she occasionally struggled with tempo. In time, she became so sure of her abilities that she played comfortably with the likes of Cecil Taylor, perhaps the most assertive free improviser.

De Barros’s presentation of McPartland’s life and career is comprehensive, balanced, and well written. He details McPartland’s early years: from birth as Margaret Turner in England (1918), through her sometimes difficult family life, through lessons in classical music at the Guildhall School in London (1935-1938), through studying and then touring with Billy Mayerl (1938), through the most important event in her life, personally and professionally: marrying the American trumpeter Jimmy McPartland in 1946. The author credits him with introducing his wife to the American jazz scene, of which he was a part, and illustrates the opposite trajectories of the spouses’ careers: his waned as hers waxed. De Barros treats Jimmy especially deftly. When discussing the trumpeter’s alcoholism and its effect on the McPartlands’ marriage, he neither dwells on it nor passes judgment. A chronicler, he does not moralize, as may further be observed in his treatment of the spouses’ infidelities. During the marriage, Jimmy fathered a child with another woman; Marian had a long affair with Joe Morello. As neither McPartland was terribly upset about the other’s unfaithfulness, there is nothing salacious in the presentation of these adulteries. The couple divorced in 1967, but remarried in early 1991, fewer than three weeks before Jimmy’s death.

In a biography, the details of the subject’s life matter. Yet Marian McPartland’s life is significant not because of her upbringing and various relationships but because of her contributions to music. These include her piano playing, which was admired by such luminaries as Duke Ellington, who listened to her at the Hickory House, and the composer Alec Wilder. Largely because of Wilder and radio producer Dick Phipps, she was asked to host Piano Jazz, though this was not her first broadcasting effort: For two years in the 1960s she hosted A Delicate Balance, a weekly two-hour jazz show on WBAI in New York. She composed music (“Afterglow,” “Ambiance,” “Twilight World”). She and her husband established Unison Records in 1948; she started Halcyon Records forty years later. She wrote about music and jazz musicians in reviews and articles and, with difficulty, in the book All in Good Time (1987), which focuses on female musicians. She was an important jazz educator, conducting workshops for students from grade school through college. She occasionally discovered students who devoted their lives to music, such as bassist Jon Burr. She was adept at selecting sidemen for her trio, players who were not only good for her but who would have rewarding careers after leaving her; they include bassists Eddie Gomez and Steve Swallow and drummers Pete LaRoca and Joe Morello. She is a focal point in Art Kane’s famous 1958 photograph of fifty-seven jazz musicians known as A Great Day in Harlem. The author treats these aspects of McPartland’s career, and more.

De Barros’s book is thorough partly because the biographer had access to the pianist. He lived with her for months, talking with her about her life and career and researching in her extensive archive. Because of her involvement in the project, one might expect him to pull punches. He does not. Her concert performances of Grieg’s Piano Concerto in A Minor, for example, generated occasionally savage reviews, from which de Barros quotes. When he thinks that criticism is warranted, he identifies flaws, though never maliciously. He terms her album Willow Creek and Other Ballads “tepid” (329). In the chapter titled “Loss,” he documents that, beginning in the late 1950s, her “life and career slowly and inexorably fell apart, until, by 1968, she hit bottom” (191). He acknowledges that she could be controlling and bullying, and cruel.

I find de Barros’s judgment generally sound, though I do not always agree with his assessments. For example, in 1995 Life magazine staged a recreation of the Great Day in Harlempicture by photographing ten of the eleven surviving musicians positioned precisely where they stood in 1958. (Sonny Rollins was on tour at the time.) To me, the later image, which shows how few of the musicians were living thirty-seven years after the original, is poignant; de Barros considers it “an unfortunate stunt” (375), without explaining why he responds to it as he does.

De Barros is, to the best of my knowledge, almost always accurate. Among the errors are these: Pierre Salinger was President Kennedy’s press secretary, not secretary of state (197); the minister to the New York jazz community was John Gensel, not Peter Gensel (347); the institution of higher learning in Athens, Ohio, is Ohio University, not the University of Ohio (352). If the book requires a second edition, these mistakes should be corrected.

I find irritating the absence of page numbers from periodicals cited in the notes at the rear of the book. Why not provide page numbers so anyone wishing to read more of what the sources relate can do so easily, without having to search through a newspaper or magazine for a specific article? Perhaps the author honored house style.

Though subsequent articles and books might expand on events in McPartland’s life that de Barros mentions or focus on aspects of the pianist’s art that do not much concern him, this biography is probably definitive.

Author = Benjamin Franklin V