Date = 19 October 2015

Author name = Amanda Petrusich

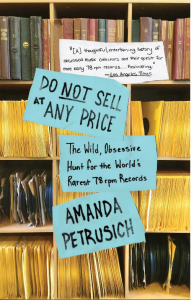

Title = Do Not Sell at Any Price: The Wild, Obsessive Hunt for the World’s Rarest 78 rpm Records

Publisher = Scribner

Review =

Until the advent of digital technology, people born after approximately 1950 bought music pressed on vinyl. Before mid-century, though, music was released on shellac, usually ten-inch brittle records that rotate at 78 revolutions per minute—give or take a revolution—and that contain about three minutes of performance per side. The time limitation was both negative and positive. Unless records were stacked on a spindle, listeners needed to tend to a record after each playing, which was cumbersome and time consuming. Yet the time constraint forced one to focus on the music and become familiar with it, a reality that does not exist when listening at one sitting to a complete LP or CD; attention wanes. In some circles, 78s have nostalgic appeal, as evidenced by the occasional DJ playing only 78s on vintage equipment at parties. In 2010 Tom Waits and the Preservation Hall Jazz Band recorded two tunes that were released on a 78, though its material was vinyl, not shellac.

Because shellac is fragile and because 78s were last mass produced in the mid-1950s, they are increasingly rare. This might not much matter in one sense because a substantial amount of the music initially released on 78 is available on-line, and, in truth, some of it, especially the mediocre popular music from the 1950s, was so ordinary that its preservation hardly matters. (With some embarrassment I admit to buying, during my teenaged years, 78s by the likes of Teresa Brewer [“Music, Music, Music”] and Eddie Fisher [“Oh! My Papa”].) Blues recordings made primarily during the 1920s and 1930s, as well as Cajun and country musics and recordings from Greece, Albania, and a few other countries from this same period—all 78s—are a different matter, as Amanda Petrusich explains in Do Not Sell at Any Price, published in hard cover in 2014 but recently released as a paperback.

Yes, used 78s can still be found at estate and garage sales as well as in thrift stores, and can be purchased inexpensively because there is a limited market for them. Rare and valuable 78s—such as those about which Petrusich writes—are not found in such places because the market for them has been cornered by a handful of passionate, voracious collectors. By focusing on these men and their pursuits—adventures is probably a better word—and what they taught her, Petrusich crafts a narrative that, while it discusses recording realities, focuses on what happened to records after they were released and their effect on this handful of dedicated men. (The author investigates why men dominate this activity.) Along the way, she becomes enamored of and transported by much of this old music that is new to her.

Petrusich lauds collectors as preservationists without whose efforts a significant segment of (mostly American) music might have been lost. One of them, John Tefteller, not only located and bought the only known photograph of Charley Patton, but he also discovered and purchased the only known copy of King Solomon Hill’s 1932 recording of “My Buddy Blind Papa Lemon.” Tefteller relates that in making these purchases “the hundred dollar bills came spilling out of my wallet,” to which Petrusich wryly responds, “It’s the sort of thing that makes you want to buy a man a cheeseburger, or at least tell him thanks” (103). Now, because of the willingness of Tefteller and others to share even their rarest items (though not by lending them), almost every recording Petrusich discusses is available at youtube.com, including “My Buddy Blind Papa Lemon.” As a result, when reading about her response to a recording, one can, after a few keystrokes, listen to it on a computer and compare one’s own reaction with hers. Granted, listening to the music this way is aesthetically inferior to hearing it on a 78 played on appropriate equipment, but there it is, ready to be enjoyed at no cost, courtesy, ultimately, of the collectors.

With one exception, the collectors Petrusich describes were previously unknown to me. The exception is Harry Smith, an odd-ball collector (most of the collectors are odd to one degree or another, though he seems odder than most) known for Anthology of American Folk Music, which he prepared for Folkways Records. Released in 1952, this idiosyncratic and influential collection—it helped inspire the folk revival of the late 1950s and early 1960s–presents music from the period 1927-1932, all drawn from Smith’s collection. Long available on CDs, the anthology influenced numerous musicians, including, according to Smith’s friend Allen Ginsburg, Bob Dylan, Ramblin’ Jack Elliott, Jerry Garcia, and Peter, Paul, and Mary. Following Smith’s death in 1991, his collection of over 13,000 78s disappeared, despite his having left most of his recordings to the New York Public Library.

Less eccentric than Smith but eccentric nonetheless, Joe Bussard is another of the collectors—perhaps the greatest collector—Petrusich presents. She did not know Smith; she knows Bussard, who owns twice as many records as Smith did. A gruff man of strong opinions (real jazz ended in 1933; country music, in 1955; bluegrass, in the late 1950s), he made one of the most impressive purchases of all time. This occurred when, on a 1966 record hunting expedition, he picked up a man walking along a road who told him that he had many old records. Bussard drove him home, where the man produced, among other things, fifteen Black Patti 78s. No known original Black Patti recording exists in more than five copies. Bussard bought all the records for $10. When word of this purchase got out, for just one of the Black Pattis—possibly the only known copy of “Original Stack O’Lee Blues,” by the Down Home Boys—Bussard received offers of up to $50,000, which he declined. Petrusich tells several fascinating, even gripping stories such as this, though none is quite so dramatic.

None, that is, except for an exploit of her own, which concerns the innocuously named Wisconsin Chair Company, located in Port Washington. In the second decade of the twentieth century it began selling phonograph cabinets, which consumers considered furniture. Soon, the company began making phonograph machines to place in the cabinets, and then, in 1917, started producing records, sold in furniture stores, to be played on the machines. They were pressed at a plant in Grafton, WI, the town where the company established a recording studio in the late 1920s. Music was released on several labels, the main one being Paramount. After the company struggled for a few years while selling popular music, in 1922 executives decided to focus on race music, as it was called—music, mainly blues, that was performed by and that appealed to blacks—though it also released other kinds of music, including country by the likes of the Dixie String Band and the Kentucky Thorobreds. Blues performers who recorded for Paramount include Son House, Skip James, Blind Lemon Jefferson, Charley Patton, and Ma Rainey. Made cheaply with inferior material, the records were released in small numbers, typically around 1,200 for each 78. Over time, the combination of poor material and few copies caused Paramounts to become scarce. Petrusich wonders—as others have wondered—what happened to the unsold records and the metal masters from which they were pressed. One rumor: they were thrown into the Milwaukee River, which flows past what was the Grafton plant. In an action that at least shows her commitment to her project, the author took scuba-diving lessons so she could search the river for something—anything—related to Paramount. She tried but failed, which could also be said of collectors’ occasional attempts to find and buy records. Her effort shows dedication, or foolhardiness, or both.

The author writes deftly about Tefteller, Smith, Bussard, and others, including herself. An outsider pleased to be introduced to and more-or-less respected by a small group of obsessive men, she marvels at what she learns and grows fond of her new acquaintances. With one collector in particular, Christopher King, she develops a genuine friendship, one that goes beyond their professional relationship. King, who introduced her to Bussard, is so committed to understanding the music he loves that, in order to write accurate liner notes for a collection of performances by the Greek violinist and murderer Alexis Zoumbas, he traveled with his family to Greece to research the musician’s life. Spending considerable money to feed his passion seems not to bother him, as may also be deduced from his willingness to pay Bussard at least $5,000 for two recordings of Cajun music—recordings he already has—because Bussard’s copies are in slightly better condition than his own. And by playing Zoumbas’s music for the author, King inspired her to write this: “And I understood, for a moment, what collectors meant when they moaned about what was lacking in contemporary music: that pure communion, that unself-consciousness, that sense that art could still save us, absolve us of our sins” (197). This statement might also partly explain the fanatical dedication to collecting by King and his associates. Yes, there is excitement in the chase, in the pursuit, and it doubtless becomes addictive. Still, there is an aesthetic reality underlying the quest, perhaps most vividly presented here in the actions of Bussard as he listens to his records in the company of King and Petrusich. He cannot sit still; he must move: “At times it was as if he could not physically stand how beautiful music was. It set him on fire, animated every cell in his body” (206).

Not only does Petrusich master an arcane topic, but she presents her material engagingly. The narrative is enhanced by an agreeable first-person voice. The reader—this reader, anyway—would like being in the company of the woman who created it. Her prose sparkles, especially when creating similes. When “like” or “as” introduces a comparison, a cliché often follows. Not so with Petrusich. Here are a few examples of her inventiveness. Listening to an analog recording on a good stereo—as opposed to hearing music on MP3–is “like delicately consuming a fancy French chocolate when you’ve only ever gnawed on Hershey bars in the parking lot of a Piggly Wiggly” (17). Accompanying Chris King as he looks for records at a flea market “is oddly thrilling, like getting tied to the back of a heat-seeking missile” (47). On seeing the Charley Patton photograph that John Tefteller discovered: “It was like looking up from a campfire, tugging a marshmallow off a stick, and spotting Bigfoot casually leaning on a pine tree outside your tent, waiting for a s’more” (101). On listening to two recordings by Alexis Zoumbas: they “sounded like someone being turned inside out, with every single one of his organs suddenly exposed to cold air” (197). A terrific writer, Petrusich has produced a masterful book.

Author = Benjamin Franklin V