Date = 24 Nov 2013

Date = 24 Nov 2013

Author’s Name = Peter Pullman

Genre = Jazz

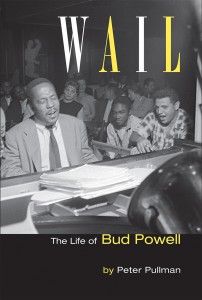

Title = Wail: The Life of Bud Powell

Publisher = Peter Pullman

Review=

Because Peter Pullman began researching Bud Powell in the early 1990s, he probably knows more about the pianist than anybody, including Guthrie P. Ramsey, Jr., whose recent The Amazing Bud Powell uses Powell primarily as a springboard for musing about genius and the social identity of bebop. Pullman’s knowledge is confirmed by his study of the pianist, an almost 500-page book published in 2012 at the author’s expense. For it, Pullman conducted approximately 800 interviews, listened to all of Powell’s recordings, and consulted seemingly everything relating to his subject. After assimilating this information, he wrote a balanced biography that details highlights as well as unpleasantnesses, of which there were many. He treats his subject’s youth, professional associations, recordings, performances, involvement with women (mostly platonic), alcoholism, occasional heroin use, musical decline, revered status in France, and more. Though Pullman is given to overstatement, a measured tone enhances his narrative, as may be observed when he details the two known times that Powell struck his mother (210, 223). He does so dispassionately, refusing to milk the events for pathos, as some writers might have done.

A schooled pianist influenced by the likes of Bach, Ravel, and Art Tatum, Powell (1924-1966) joined the band of his brother William in 1940, played in his native Harlem at Minton’s Play House and Monroe’s Uptown House when bebop was being developed there, and joined the Sunset Royals before entering the big time with Cootie Williams in 1942. Also with Williams irregularly during this period was Charlie Parker, whose new approach to music Powell embraced. His life changed in 1945, when he was reportedly beaten by police after being arrested for drunkenness. The resulting headaches and strange behavior led to hospitalization and to a diagnosis of manic depressive psychosis. Thus began serious emotional problems that lasted for the remainder of his life.

Yet off and on for approximately a decade beginning in 1947, Powell led impressive trio sessions for such labels as Roost, Clef/Norgran/Verve, Blue Note, Debut, and RCA. His bassists included Ray Brown, Paul Chambers, George Duvivier, Percy Heath, and Curly Russell; Art Blakey, Kenny Clarke, Roy Haynes, Buddy Rich, and Max Roach were among his drummers. An album of Powell’s solo performances was recorded in 1951. Powell’s reputation rests primarily on music from these sessions. From the beginning of his career, however, leaders recognized the pianist’s ability, as the many impressive recordings on which he appeared as sideman illustrate. These include Cootie Williams’s “Round Midnight” (1944), Dexter Gordon’s “Long Tall Dexter” (1945), Sarah Vaughan’s “If You Could See Me Now” (1946), J. J. Johnson’s “Jay Bird” (1946), Fats Navarro’s “Boppin’ a Riff” (1946), Charlie Parker’s “Donna Lee” (1947), Sonny Stitt’s “All God’s Chillun Got Rhythm” (1949), Quintet of the Year’s “Wee” (1953), Coleman Hawkins’s “All the Things You Are” (1960), Oscar Pettiford’s “Blues in the Closet” (1960), Charles Mingus’s “I’ll Remember April” (1960), Don Byas’s “I Remember Clifford” (1963), and Dizzy Gillespie’s “Groovin’ High” (1963). Among the most significant musicians in jazz history, these leaders could have used any available pianist they desired, but they chose Powell. Why? Because of his inventiveness and his expressive, intense style, qualities that made him the preeminent bebop pianist and make his most accomplished music enduring. Still, his recordings and live performances were hardly consistent, and his life was erratic. In Wail, Pullman provides all the details of Powell’s life and career that most people would wish to know, but is most impressive and valuable when discussing the problems that led to the pianist’s decline--mainly his emotional problems, which led to hospitalizations. Pullman had access to medical records, some willingly provided by institutions, but others relinquished only after he won the suit he filed against the New York State Office of Mental Health in the New York Supreme Court. As a result, he bases his comments on the best possible evidence.

That Powell was emotionally unstable is not news; fortunately, Pullman provides many details about this instability that were not previously known. From the medical records he learned, for example, about the pianist’s difficulty with what psychiatrists call ideas of reference (considering ordinary events as of great personal significance). In 1947, drinking exacerbated this problem to the degree that in a club Powell fought a patron over the issue of race, an action that led to his confinement in the state hospital in Creedmoor, NY. Because of his disruptive behavior while still there the next year, he was forced to wear a straightjacket; then, he underwent two series of electroconvulsive therapy (shock treatments). On the topic of the pianist’s emotional state, Pullman notes that Powell was predisposed to a nervous breakdown; he also believes that Powell was disserved by judges who committed him to psychiatric hospitals and that the pianist received inadequate screening during the admission processes. I find his treatment of Powell’s emotional problems sound (I am neither a psychiatrist nor a mental health professional), though I wonder if some of his judgments of medical personnel are too harsh.

Powell’s greatest recordings (including “All God’s Chillun Got Rhythm,” “Parisian Thoroughfare,” and “Un Poco Loco”) rank with the best work of any jazz pianist, which makes Powell’s artistic decline all the sadder. Pullman notes that it began in 1953, the year Powell performed at Massey Hall in Toronto with his trio and with a quintet featuring Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie. (Pullman believes that Powell’s solo on “Salt Peanuts” with the quintet “ranks with his greatest, regardless of context” [185]). The author identifies strong and weak performances from then until the end of the pianist’s career. At his last recording session, as leader in January 1966, Powell played so poorly that Pullman concludes that none of the music “should have been considered for release,” though the session was released, on Mainstream. He further states that the music on this album constitutes Powell’s “last, embarrassing attempt . . . to make music” (376). While I agree, to this statement I would add “sad” between the first two words.

As an examination of Powell’s life—professional and personal--Wail will probably never be surpassed, which is not to say it is perfect. (What is?) Pullman makes claims he cannot support (“Powell gave his performances every drop of sweat that he had” [150]); treats George Shearing contemptuously (152, 183); states what people thought when he has no way of knowing (“Powell had to be thinking of the long, lonely voyage back to New York” [208]); criticizes Powell’s fan Evelyn Glidden gratuitously (237); dismisses people with a single unflattering adjective (“the pedantic Kurt Mohr” [290], “the bourgeois Paudras” [337]); fails to define terms (October Revolution [358, 372]); and treats Leonard Feather’s Blindfold Test unfairly (382). He also seems credulous, as when believing that Thelonious Monk cried because of his supposed pianistic inferiority to Powell (303) and that Powell recited the Gettysburg Address from memory when asked to do so (420). In all likelihood, a copy-editor would have challenged Pullman on some of these points and made stylistic suggestions, such as eliminating “, though,” in most instances. Granted, Pullman published the book himself, so the cost of engaging a copy-editor for his long manuscript probably would have been prohibitive. Ultimately, these and other infelicities are relatively insignificant in the context of the book’s strengths, especially its comprehensiveness and detail.

Had Powell not been a gifted person, his life would hardly warrant comment. Yet because he was an accomplished pianist, it assumes importance. Thus, Pullman’s book is well worth reading by anyone interested in jazz, the creative process, or emotionally impaired artists. Though one would gain a full sense of Powell from it, it might best be read in conjunction with listening to his recordings, most of which are readily available. (A Powell discography would have enhanced the book.) Doing so would permit one to hear his greatness (and not-so-greatness) and understand why Pullman evaluates the pianist’s artistry as he does.

Author=Benjamin Franklin V