Date = 25 February 2014

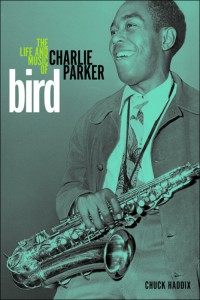

Author = Chuck Haddix

Genre = Jazz

Title = Bird: The Life and Music of Charlie Parker

Publisher = University of Illinois Press

Review=

Charlie Parker (1920-1955) is among the most documented jazz musicians. During a relatively brief recording career (1940-1954), he participated in approximately 250 recording sessions, around 175 as leader. He has been written about extensively, including in books by people with first-hand knowledge of him (such as Ross Russell) and by major critics (such as Gary Giddins). Several Parker discographies have been published. Carl Woideck compiled a collection of writings about him; Ken Vail chronicled his life. Mark Miller detailed his time in Canada. Even a book reproducing his memorabilia has been published. The list goes on. Chuck Haddix’s Bird is one of the most recent books to focus on Parker.

Now, almost sixty years after Parker’s death, a writer needs to have significant new information about—or a fresh approach to--the musician before undertaking a book about him. Because of the author’s research in census records, city directories, and other documents, Bird provides new information, especially about Parker’s early years. All knowledge is good, but the facts Haddix discovered are mostly trivial.

Here are some facts Haddix provides, all of which are new to me. Commenting on the Hannibal Bridge, he notes that “in 1917, at the peak of rail traffic, 271 trains passed daily through Union Station, the massive stone Beaux Arts train station located on the southern edge of downtown” Kansas City, Missouri (7). He records that “as a teenager” in Oklahoma, Parker’s mother “worked as a maid for a household of six headed by Mary H. Morris on Main Street in McAlester, the county seat” (7), and that Parker’s father, “born in 1886,” resided “in a rooming house at 311 West Sixth Street in the heart of a crowded slum on the northern rim of downtown Kansas City, Missouri” (7-8). He observes that Parker played in the band at the 1935 high school graduation of Rebecca Ruffin, who married him the next year; the band performed Elgar’s “Pomp and Circumstance” and the first theme from Coleridge-Taylor’s “An Imaginary Belle” (17). (Does Haddix mean “Scenes from an Imaginary Ballet”?) He pinpoints the location of Musser’s Ozark Tavern, where, in 1936, Parker was en route to play when he was injured in an automobile accident that killed a companion: “three miles south of Eldon, Missouri, at the junction of Highways 52 and 54” (24). Haddix provides numerous addresses, such as those for Kansas City Musicians’ Local 627 (18) and Lucille’s Paradise (28), the Kansas City club where Parker joined the band of Buster Smith.

As the book progresses, the author presents less new information and increasingly treats familiar Parker material: humiliation by Jo Jones, discovering how to create music he had been hearing in his mind by playing “Cherokee” in a new way, various band affiliations, how he became known as Yardbird (later shortened to Bird), the Benzedrine episode with Rubberlegs Williams, the engagement at Billy Berg’s, confinement at Camarillo State Hospital, recording sessions, relationships with wives and Chan Richardson, death in Hotel Stanhope, and so forth. Though he interviewed people who knew Parker, including Jay McShann, Haddix based his treatments of events mainly on secondary sources, such as Robert George Reisner’s Bird: The Legend of Charlie Parker (1962), which includes various people’s recollections of Parker, and Mark Miller’s Cool Blues (1989).

When presenting information from secondary sources, Haddix sometimes seems credulous, as when recounting Parker’s conversation with Einstein (62-63), sleeping under the bandstand during a performance by the Earl Hines band (64), and sleeping all day in a telephone booth (71). These things might have happened, though in each instance Haddix relies on a single source: first, Junior Williams; second, Billy Eckstine (when citing the source of Eckstine’s quotation, Haddix records the wrong page number at n. 12 on 171; Eckstine’s words are from Reisner’s Bird, 85, not 17); third, Art Blakey. Providing another source for each would have bolstered the author’s claims.

Because the sub-title implies full treatment of Parker’s life and music, it misleads: Bird is primarily biographical. When discussing music, Haddix mostly treats externals, as the following illustrates. For Savoy Records, Parker led his first commercial session on 26 November 1945. Haddix notes that Parker composed tunes for it, addresses the confusion over which pianist (Argonne Thornton or Dizzy Gillespie) and trumpeter (Gillespie or Miles Davis) perform on which selections, states that Parker had horn problems, identifies the number of takes for each tune, believes that Parker undermined the session by approaching it haphazardly, and points out that reviewers praised Parker’s solos while “panning the overall result” (83). The author offers what passes for analysis when commenting on “Now’s the Time,” noting only that Gillespie’s altered chords caused Davis to play “out of key” (82), though he does not demonstrate cause and effect. Haddix thinks that this recording highlights “Charlie’s Kansas City roots and deep feeling for the blues” (82), but without explaining how.

Though I acknowledge the difficulty of conveying, in prose, the nature of music, Haddix’s characterization of Parker’s gives little if any sense of its gloriousness—and it is this quality that makes the saxophonist’s life worth documenting. Haddix does not even mention that Parker’s solo on “Ko Ko” (from the “Now’s the Time” session) is widely considered one of the most impressive and important solos in jazz history. It is so highly regarded that it was in the first group of recordings selected for the National Recording Registry at the Library of Congress (see item 36 at http://www.loc.gov/rr/record/nrpb/registry/nrpb-2002reg.html; accessed 24 February 2014). The Library of Congress justifies its inclusion by stating that it “signaled the birth of a new era in jazz—bebop.” Though the accuracy of this claim can be debated, Haddix ignores the recording’s significance. To him, it is just another Parker recording. He also fails to indicate that two of the tunes Parker wrote on the spur of the moment for this session—“Billie’s Bounce” and “Now’s the Time”--are so appealing that each has been recorded hundreds of times. They are part of the jazz repertoire, as anyone who has listened to much jazz can attest. (Ted Gioia identifies them as such in The Jazz Standards [2012].) “Billie’s Bounce” was inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame (2002). In other words, Haddix does not attempt to do justice to Parker’s music.

This book needed copy editing. For example, Haddix writes “fed up towing the Jim Crow line” (69; the correct word is “toeing”) and “he was getting ringing wet” (72; “wringing”). Because he quotes the latter correctly from a published source, “[sic]” should have been inserted after “ringing” to indicate awareness—if there was awareness--of the error in the source material, an interview with trombonist Trummy Young. Singer Ethel Waters is identified as Ethyl (77). Haddix twice states that the Kansas City Call was an African American newspaper (17, 28) and four times notes that Emry Byrd was known as Moose the Mooche (86, 95, 146, 184). The given name of John S. Wilson is misspelled (171, n. 29). No publication date is provided for Chan Parker’s My Life in E-Flat (172, n. 41). The index identifies the radio program Bands for Bonds as Bands for Bond and alphabetizes Ross Russell according to his given name. Though relatively unimportant, these and other infelicities should not occur in a book published by a major university press.

Well-written and generally accurate, Bird will benefit readers who desire an overview of the musician’s life and career. Those already familiar with Parker will learn from it primarily specifics about his early years, such as addresses of various places. It is not the book to consult for significant new biographical information or for a discussion of or insight into his music.

Author = Benjamin Franklin V