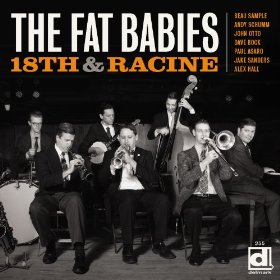

Artist name = The Fat Babies

Genre = Jazz

Title = 18th & Racine

Record company = Delmark

Review =

Why is it that some established forms of improvised music are more valued than others? Though bebop developed in the early 1940s, for example, it is possibly the form of jazz played most frequently. Traditional jazz, however defined, is less highly regarded. One reason for this disparity might be that the more modern music is complex and therefore demanding while the older is sometimes simple and presumably easy to play. Bebop is still capable of yielding surprises; traditional jazz, less so. On “High Society,” can any traditional clarinetist escape the influence of Alphonse Picou’s solo from the distant past?

Whatever the answer(s) to the question, traditional jazz continues being performed by serious musicians. Vince Giordano’s Nighthawks is probably the most notable traditional group; bassist Beau Sample’s Fat Babies is another one. Founded in 2010 and headquartered in Chicago, this septet plays compositions mainly from the 1920s and early 1930s. Its music is vital partly because most of its repertoire, as represented on 18th & Racine, is not overly familiar. Yes, “Stardust” is one of the most popular tunes in all of American music and anyone interested in traditional jazz doubtless is aware of “Nobody’s Sweetheart,” but the remaining thirteen selections are less well known. Among them are creations by such stellar musicians as Fletcher Henderson, James P. Johnson, Jabbo Smith, and Clarence Williams.

So what does the band bring to these more-or-less neglected compositions from long ago? At least two things: First, it plays well and energetically; second, it performs some tunes in a manner consistent with the original recordings of them while refashioning others. Consider the second point. Despite being twenty seconds longer than Jabbo Smith’s recording of “Till Times Get Better,” the septet’s version follows the structure of Smith’s. Both begin with a piano introduction (including three identical opening notes). Then, the cornet states the melody, a musician sings, the clarinet solos, and the cornet concludes the piece. The group takes liberties with Fletcher Henderson’s “The Stampede,” giving the opening melodic statement to the cornet rather than the ensemble and otherwise redistributing the solos among the horns; the new recording is over a minute longer than Henderson’s. In other words, the band’s approach to its material is not predictable.

Two selections require special comment. The corny vocal on “I’ll Fly to Hawaii,” recorded initially by Brad Gowans in 1926, makes it irredeemable. This might be the first recording of the tune since the second recording of it--by Julian Fuhs in 1927. The reason for its neglect is obvious. With many old songs worthy of reconsideration, I wonder why leader Sample chose “I’ll Fly to Hawaii” for inclusion on this CD. James P. Johnson’s “Blueberry Rhyme” is a piano solo by Paul Asaro, backed only by drummer Alex Hall on brushes. The composer recorded it twice (1939, 1943), both times as an unaccompanied piano solo. It became something of a favorite of Asaro, who recorded it at least four times as leader, all in 2004. That his and Hall’s version is polished therefore comes as no surprise.

The music on 18th & Racine shows that in the hands of spirited instrumentalists, traditional jazz played unpredictably is still viable.

Author = Benjamin Franklin V