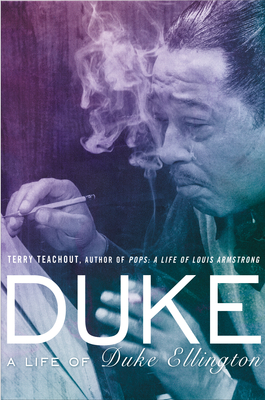

Author = Terry Teachout

Genre = Jazz

Title = Duke: A Life of Duke Ellington

Publisher = Gotham Books

Review =

Duke Ellington is arguably the most important person in jazz history. Without question the major jazz composer, he would almost certainly be enshrined in any pantheon of American composers. He led a band from the 1920s until 1974, the year he died, partly so he could hear his creations played by superior players, whose individuality inspired him to write tunes with them in mind, such as “Concerto for Cootie” for trumpeter Cootie Williams. If he did not always acknowledge their contributions to compositions credited only to him, he paid them well and abided their idiosyncrasies and indiscretions to the degree that his major players stayed with him for decades. Harry Carney, for example, was the baritone saxophonist from 1927 until after the leader’s death. When a star soloist resigned, it was news, as when Williams departed for Benny Goodman’s group in 1940: the jazz press noted it, and Raymond Scott even wrote a tune titled “When Cootie Left the Duke.” In time the defectors, including Williams, returned, partly because they were unsuccessful away from the band, partly because of the security Ellington offered, and partly because he provided a context for them to perform to best advantage. He worked tirelessly, distracted from music seemingly only by sex, for which he would walk, as he once said, past money to attain. Even though he accurately presented himself as dignified and sophisticated--cultured, refined, and elegant--so he and by extension his music would reflect well on his race, he was impenetrable. He kept people at charm’s length, seldom revealing much about himself, even in Music Is My Mistress, his 1973 autobiography. In Duke, Terry Teachout concludes that “everyone knows him—yet no one knows him. That was the way he wanted it” (361).

Ellington might have been inscrutable, but Teachout’s admirable narrative conveys much of what is known about him, though most of the information, by far, concerns his professional life, as it should. While interesting, his little-known personal life—the never-divorced wife who once slashed his face; the discarded lovers who married his sidemen, including trombonist Lawrence Brown—is mostly irrelevant to what makes him important: his music. On this topic, the author is compelling. Though he details aspects of numerous recordings (recordings constitute the proof of Ellington’s greatness), he does not mention every session, or every tune from the sessions he does discuss. Mainly, he treats highlights. When focusing on “Ko-Ko” (1940), for example, he comments on the opening riff and the dissonant piano in the fourth chorus before concluding that this performance is “a relentless procession of musical events that contains not a wasted gesture. Every bar surges inexorably toward the final catastrophe, after which no response is possible but awed silence.” He terms this “the greatest of Ellington’s three-minute masterpieces” (208). As this statement indicates, he has beliefs--and provides reasons for them. Generally, though, he agrees with the critical consensus, as when valuing most highly the band that was active circa 1940, the one now known as the Blanton-Webster band for two of the most important sidemen, bassist Jimmy Blanton and tenor saxophonist Ben Webster. Agreement with the majority view is inevitable because Ellington has been taken seriously for a long time and has been written about voluminously. Men of strong opinions, James Lincoln Collier and Gunther Schuller are just two of the writers who have addressed Ellington and influenced opinion about him. Further, the music speaks for itself: The qualitative difference is obvious between such early classics as “Creole Love Call” (1927) and “The Mooche” (1928) and such late albums as Paris Blues (1961) and Hits of the 60’s This Time by Ellington, which is also known as Ellington 65 (1964). To his book, Teachout appends a list of fifty key recordings arranged chronologically, though he does not indicate what he means by “key.” Does he mean that these recordings are, to him, Ellington’s best? The most important in the development of the leader’s career? Something else? No matter what he means, he intends to commend them. In doing so, he provides guidance to readers unfamiliar with Ellington’s music; the list will also possibly inspire debate among initiates who will doubtless agree that most of the recordings the author mentions are significant. Most of the recordings, but not all of them: I, for one, do not value the 1968 Second Sacred Concert. I also think the album Money Jungle (1962) is effective as a whole, not just for “Fleurette Africaine.”

Despite being unable to detail much personal information about the adult Ellington, Teachout treats his relationships with professional associates, including two who operated largely behind the scenes: his manager and major collaborator. He explains Irving Mills’s importance by demonstrating how the manager helped establish the leader’s image and promoted Ellington by, among other things, getting him good bookings and arranging for the band to appear in movies. Teachout also explains why Mills is identified as co-composer of tunes written by his employer, such as “Mood Indigo.”

Though some members of the Ellington organization despised the leader (Lawrence Brown is one who did), others idolized him. Paramount among the latter group was composer and pianist Billy Strayhorn, who auditioned for Ellington in late 1938 by playing two Ellington tunes plus two of his own compositions, “Lush Life” (written at eighteen) and “Something to Live For.” Ellington soon hired him. Strayhorn wrote numerous pieces for the band, including “Take the A Train,” which became its theme, and “Chelsea Bridge”; he collaborated on others, such as “Rocks in My Bed.” In time resenting Ellington’s paternalism and co-opting of his compositions, Strayhorn left his mentor in the early 1950s and began writing on his own. Later, the relationship was renewed; they collaborated on the suite Such Sweet Thunder (1957) and the popularly successful The Nutcracker Suite (1960). Despite their differences, Ellington was devastated by his associate’s death (1967). Distraught, he thought himself incapable of delivering the elegy he wrote, so he “sat in stony silence as his heartfelt words were read out loud to the mourners” (334). Soon thereafter, Ellington recorded an album (. . . And His Mother Called Him Bill) devoted to Strayhorn’s compositions. On it, he plays “Lotus Blossom” so movingly that it stands as one of the most emotional performances of his long career.

Teachout makes many astute observations. One concerns how Ellington’s compositions differ from those of all other big-band leaders: “instrumental color” (213). Another explains how Ellington attained this coloring: while arrangements performed by other bands kept the various sections (trumpet, trombone, woodwind) separate, Ellington “mixed the sections of his band together” (213). The author also observes that Ellington was not a natural melodist and that he could not grasp the necessity of writing musicals that are driven by the songs. Jump for Joy is an example of this failure. He explains how Ellington deftly solved problems caused by the 1941 creation of Broadcast Music Incorporated to compete in the licensing of songs with the established American Society of Composers and Publishers. (Ellington was a member of ASCAP.) Additionally, he gives some inside information about Ellington’s musicians: the hiring of Rex Stewart angered Cootie Williams, Barney Bigard was a prankster, and Tricky Sam Nanton was an intellectual. He explains why Ellington valued the valve trombone, and notes that he wore a girdle.

In addition to providing a comprehensive view of Ellington and his music, Duke is well written and easy to read, even by those unfamiliar with musical terminology and who cannot read music. “Ostinato” (162) is probably the most demanding musical term Teachout uses; nowhere is there musical notation. He explains the method he used when writing the book: It “is not so much a work of scholarship as an act of synthesis, a narrative biography that is substantially based on the work of academic scholars and other researchers” (363), though he acknowledges his responsibility for interpreting this material. His indebtedness to the work of others is evident in eighty pages of notes, so anyone wishing to confirm the author’s statements may do so. A reader may easily evaluate Teachout’s interpretations of Ellington’s music by accessing much of it on youtube.com, and for this reason I recommend reading the book while seated near a computer. Want to hear Bing Crosby singing “St. Louis Blues” (1932) with Ellington? It is on YouTube, as is “Old Man Blues” (1930), of which Teachout makes much. What about Ellington’s presence on film? The obscure Symphony in Black (1934) is there, as are two movies from 1937, The Hit Parade and Record Making with Duke Ellington and His Orchestra.

Teachout concludes his narrative perfectly. Returning to the impossibility of knowing many facts about Ellington, the author notes that Ellington actually revealed himself: “He left behind his music, the only mistress to whom he told everything and was always true” (361).

Author = Benjamin Franklin V